Business rules in system architecture

Don’t hardcode business logic. Bet on DMN and Drools.

Abstract

In the world of software architecture and engineering, there is often a temptation to solve every problem with more lines of code in programming languages. However, when business rules specific to a supported industry come into play, the imperative approach becomes a trap. How do we separate “what” the system is supposed to do from “how” it does it? The answer lies in engines for describing and processing business rules and open standards—such as DMN (Decision Model and Notation).

Business description of the system

Every experienced developer knows this scenario: after a discussion with a business analyst, a requirement appears to modify the application’s behavior - for example, changing the parameters of a product that determines a specific production method in a factory. The change seems trivial - it is often just a single attribute. However, from a technical point of view, this means modifying the source code, rebuilding artifacts, running tests, and fully deploying a new version of the application. This is a classic example of tight coupling between the technical architecture and the business architecture. In an ideal world, these two entities should live independently side by side.

The original sin - “hardcoding” business logic

The traditional approach to implementing business logic involves mapping it into conditional statements within the general-purpose language used by the development team to build the application. Let’s look at a simple example in Java. We want to grant a discount based on the customer type and the cart value. Below is the imperative approach—placing business logic directly in the code, illustrated by calculating a discount for different classes of customers:

public BigDecimal calculateDiscount(Order order) {

if (order.getTotal().compareTo(new BigDecimal("1000")) > 0) {

if ("VIP".equals(order.getCustomerType())) {

return new BigDecimal("0.15");

} else if ("REGULAR".equals(order.getCustomerType())) {

return new BigDecimal("0.05");

}

}

return BigDecimal.ZERO;

} At first glance, the code is readable. Problems begin when there are many more rules, dependencies form between them, and they change frequently. Such code becomes very difficult to maintain. As the system grows and evolves, a realization emerges: changing business logic should not require recompilation!

Why open standards (DMN) instead of custom DSLs?

Many architects facing this problem might suggest: “Let’s write our own rule parser! Let’s create our own Domain-Specific Language (DSL) in a format familiar to business people—like XML or JSON—so they can edit it.”

It is important to remember that creating your own rule engine involves enormous costs: the necessity of building parsers and a lack of compatibility with market tools. Instead of reinventing the wheel, it is worth leaning towards open standards.

This is where DMN (Decision Model and Notation) enters the scene. DMN is a standard managed by the OMG (Object Management Group). This is the same organization that worked on the well-known UML notation. The first versions of DMN appeared in 2015. Although a period of over 10 years is an eternity in the IT industry, in the case of standards, it implies maturity, stability, and broad tool support.

DMN allows for modeling business decisions in a way that is understandable to both a computer program and a human (e.g., diagrams and decision tables).

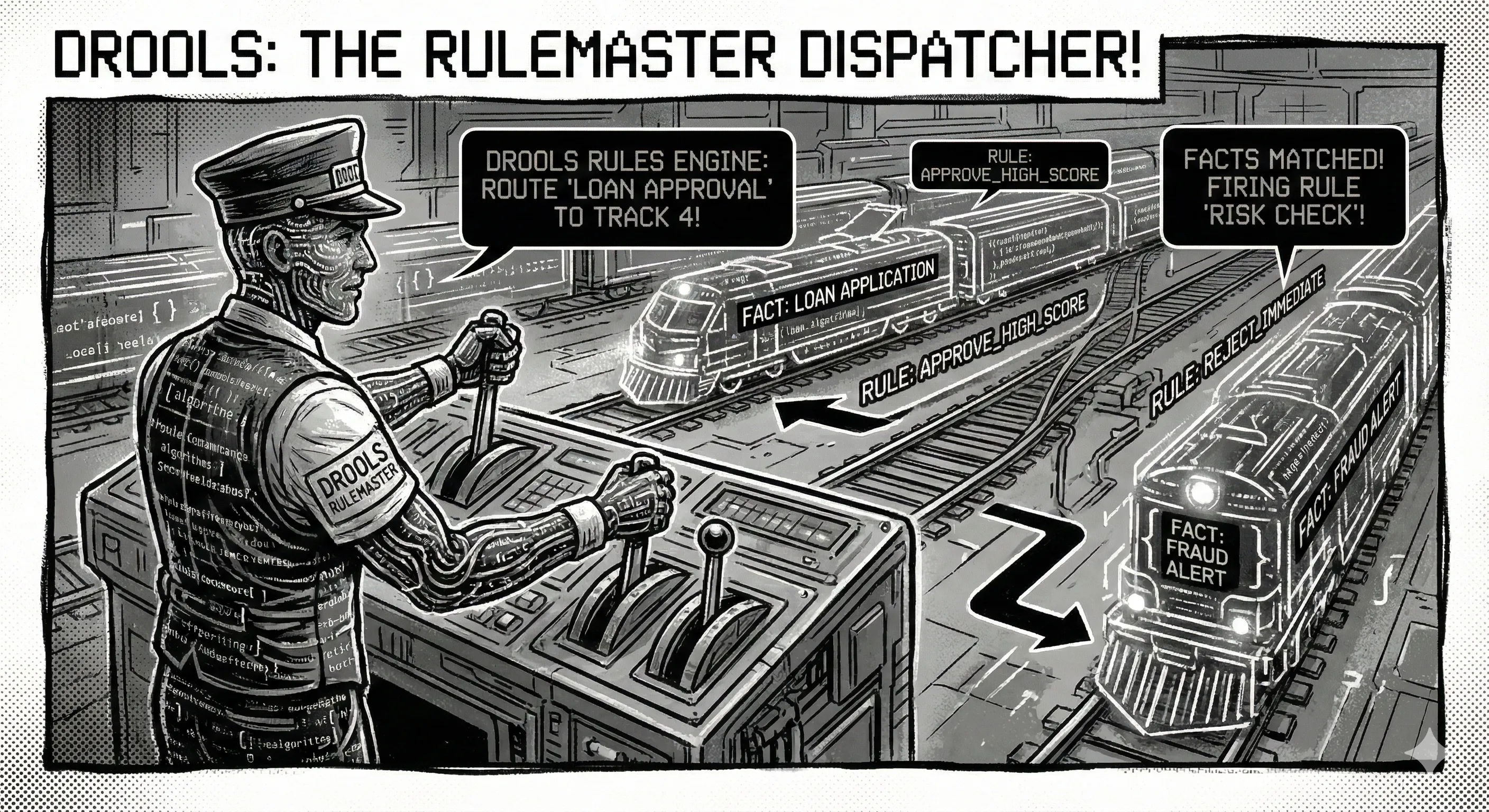

Drools: the engine that drives DMN

The most popular rule engine currently supporting DMN is Drools (part of the KIE/JBoss ecosystem). Drools allows for the extraction of business logic—the application becomes merely a technical layer that sends data (facts) to the Drools engine and receives a decision (objects, lists, parameters). Let’s see how the same discount problem looks in the world of Drools rules.

Classical approach: Drools Rule Language (DRL) format

Drools has its native rule definition format (.drl files). This is a declarative approach. We do not focus on how to check conditions, but on what should happen when conditions are met.

A fragment of rules granting a discount based on customer type:

import pl.psti.learning.model.Order;

import pl.psti.learning.model.Discount;

rule "VIP Discount over 1000"

when

$o : Order( total > 1000, customerType == "VIP" )

then

insert(new Discount(0.15));

end

rule "Regular Discount over 1000"

when

$o : Order( total > 1000, customerType == "REGULAR" )

then

insert(new Discount(0.05));

endThe Drools engine, using internal, optimized algorithms, instantly matches facts to many similar rules.

Decision tables

Drools also allows defining logic in the form of a Decision Table. Such a table is not “code” in the programming sense—it is a matrix that a business analyst can edit in Excel or another editor.

Example decision table for our scenario:

| U | Typ Klienta (Input) | Wartość Zamówienia (Input) | Rabat (Output) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ”VIP” | > 1000 | 0.15 |

| 2 | ”REGULAR” | > 1000 | 0.05 |

| 3 | - | <= 1000 | 0.00 |

For the Drools engine, this description format is directly executable, analogous to the .drl notation.

What dd we gain by separating code and business rules?

Implementing a rule engine like Drools and relying on the DMN standard is often a strategic architectural decision for a system. When deciding on such an implementation, it is worth considering the following benefits:

- Separation of the rule deployment cycle from the application deployment cycle: The application might be deployed, for example, once a week. Rules can be updated daily without triggering CI/CD pipelines (so-called hot deployment).

- Business Testing: Rules can be tested automatically by checking if expected outputs are received for given inputs, without the need to run the entire infrastructure.

- Consistency and a Single Source of Truth: The same rule file can be used by the system and can also be used to generate documentation.

- Safety: By separating technical logic from business logic, we reduce the risk of errors in the main application code.

Summary

System flexibility is not a feature added at the end of a project. It is the foundation of correct architecture. Using the DMN standard allows for a very effective separation of what is technical (scalability, security, interfaces) from what is business (decisions, process flows).

In times when business changes faster than ever, keeping decision logic in source code is technical debt. Therefore, it is worth choosing open standards instead of building impressive structures made of if statements.